Jallianwalla Bagh ”“ a hundred years.

By Sudha Kumar

Jallianwalla Bagh ”“ a hundred years on, is a poignant reminder of the price of our freedom, our birthright.

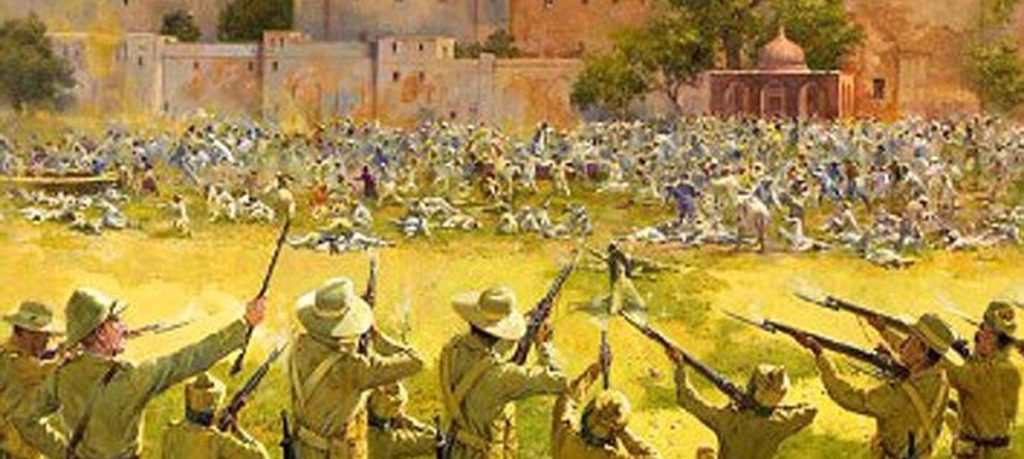

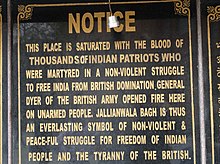

On April 13, 1919, British troops fired on a large crowd of unarmed Indians in a walled space Jallianwala Bagh in Amritsar, Punjab, killing several hundred people, men, women and children, and wounding many hundreds more. In it is situated a well where people jumped in dozens, to save themselves from the bullets fired indiscriminately at them by the troupes, with the main entrance blocked so that no one could escape the walled compound, some tried to clamber the walls as they got shot.

The lives that were lost on that fateful Baisakhi Day in Jallianwallah Bagh in Amritsar can never be replaced. They were common people who got together to peacefully protest in response to the most unjust Rowlatt Act. This act effectively authorized the British government to imprison any person suspected of terrorism living in British India for up to two years without a trial, gave the imperial authorities power to deal with all revolutionary activities, and detain anyone as a preventive measure. It was also called the ”˜Black Act’. For all the right reasons.

2019 marks a hundred years of that massacre.

One hundred years is a long time in any political history. In the case of India and her freedom struggle which spanned close to a hundred years, (even if the sepoy mutiny of 1857 is considered as the first war for independence), the period is strewn with a myriad events of admirable resolute and gut wrenching pain.

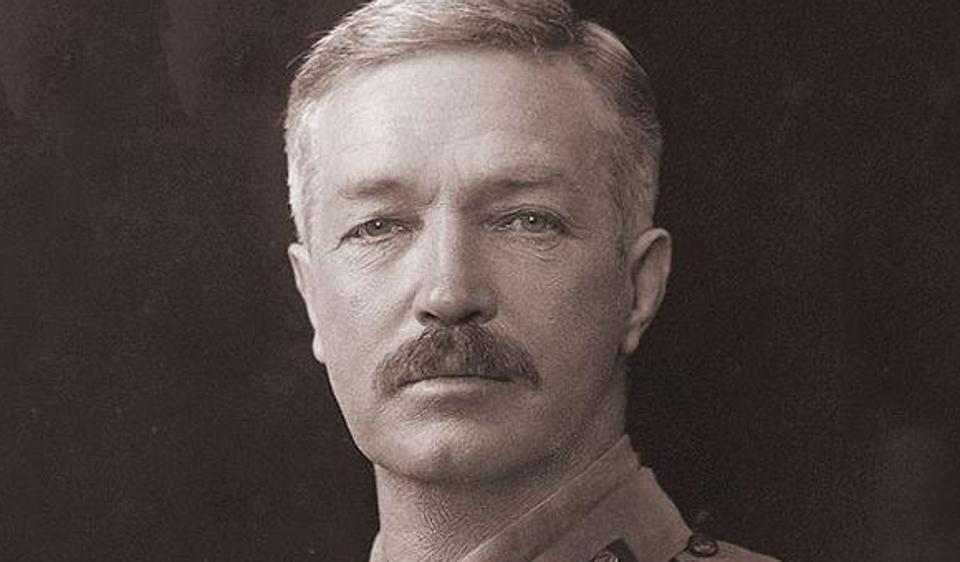

And yet, the Jallianwallah Bagh massacre stands out in India’s history for its brutal violence and its uniqueness. Because it was the single event that portrayed the sheer arrogance and brutality of British colonial power, and of the resoluteness of the Indian people. Because it unified the Indians in their struggle like no other event, and made Indians freedom fighters out of the millions. It demonstrated the callousness of a colonial empire and its representative instigator General Reginald Dyer. It goaded the Nobel Prize winning poet Rabindranath Tagore to return his Knighthood to the king, and a host of Indian appointees to British Offices to walk away from their posts. It revealed how little the British valued Indian lives. It rendered clarity to the fact that India had to rid herself of an empire that was evil. Mahatma Gandhi now saw freedom synonymous to truth, and the imperial empire satanic. It was a decisive moment when the Indian jewel alienated herself from the British crown.

Freedom comes at a price.

For the families affected, the loss was physical, mental, emotional, economical and national. There are few alive to tell the story.

And yet it is timeless. The memory singed into the psyche of a people.

But what is the relevance of this event in 2019? Beyond the commemoration and poignant reminder.

UK Prime Minister, Teresa May, on 10 April 2019, in the throes of the Brexit drama, found a few minutes and made it a point to express ”˜deep regret’. And yet it fell short, that little bit short.

So how does a people or a country make good a grave injustice of a hundred years?

Perhaps by learning the good lessons from the injustice, by not ignoring or validating it. Not forgetting. Teaching the schoolchildren of both countries, what built their homeland. Like the German school children who are taken to the concentration camp sites to teach them a painful historical reality that should never occur again.

Perhaps a gesture of atonement- an apology. Similar to Justin Trudeau’s over Komagata Maru, or Kevin Rudd’s to the ”˜Stolen Generation’. Because an apology is a simple act that convinces the other of regret. It has the power to bridge differences across time and people. It goes far beyond just the use of the word ”˜regret’.

Perhaps by returning the priceless artefacts that were looted from the colonies spread across the world. Artefacts that were mere valuable objects to the imperial power, but to their subjects were symbols of identity and history of a people, of their intellect and culture. The Kohinoor still sits on the Queen Mother’s crown in the Tower of London. It is a powerful reminder of the brutal, racist, oppressive rule that colonialism was. And dare I say for that very reason perhaps is evidence of the same until it gets back to its rightful owners.

A hundred years on, as we bow in reverence to the lives that were taken at Jallianwallah Bagh, let us take pause and remember that our freedom came at a price.

Lest we forget.

Short URL: https://indiandownunder.com.au/?p=13137