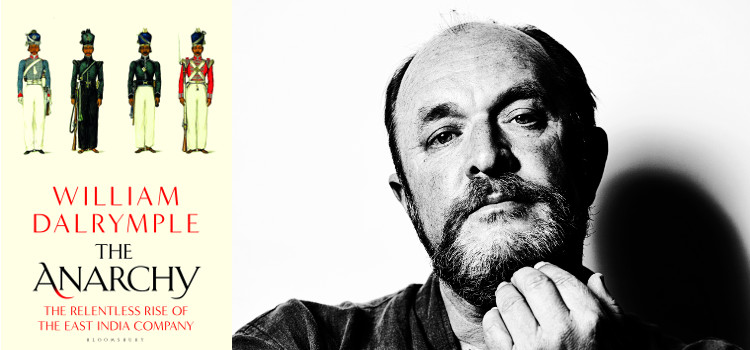

”˜The Anarchy’ By William Dalrymple – The story of enslaving of a country and her people.

By Sudha Kumar.

”˜The Anarchy-The relentless rise of the East India Company’ by William Dalrymple, is the story of a country and her people. One of the richest countries of the 18th century that was a leader in manufactured textiles and producer of a quarter of the world’s manufacturing, with her cities being the megacities of the day. A country that was for two hundred years systematically looted, plundered, oppressed and ironically came to be described as the ”˜Jewel in the British Crown’. It is the story of the enslaving of 18th century India by a small merchant company that set out to trade with the East. Of how a small corporation brought a rich thriving empire and her people to their knees. A story of power, profit, politics and racism. And as Dalrymple says in his book ”˜four hundred and twenty years after its founding, the story of the East India Company has never been more current’.

I spoke with author William Dalrymple about ”˜The Anarchy’. Here are the excerpts.

1.What inspired you to write The Anarchy?

I’ve been writing about the East India Company for about twenty years now and have been doing these ”˜micro histories’. ”˜White Mughal’ was the story of the love affair in Hyderabad in 1798-1805. The ”˜Last Mughal’ was the story of the great uprising in Delhi in 1857.and ”˜Return of the King’ was about the invasion of the East India Company’s invasion of Afghanistan, just three years 1839 to 42.

It was about time, if I was ever to do it, take a big picture, do a big sweep, about what, as a whole, the East India Company did to India. Both the British and the Indians think that ”˜The British’, with a capital T and a capital B, conquering India”¦. For the British and Victorian period this was a story of national glory, for Indians it was a story of national oppression and ultimately liberation. But both saw it as a national story, what both sides forgot was what was well known in the eighteenth century, far more shockingly this was a ”˜corporate’ story, this was the story of how one London business took over the entire Mughal empire. It is the most extraordinary story in history. It is sort of.. phenomenally unlikely, particularly, when the company is founded, Britain controls about 1.7% of world GDP and the Mughal empire about 37%, and so this is a phenomenal story of how one terribly ruthless London corporation looted, plundered and conquered the richest empire in the world.

How on earth did that happen? That’s the question I am trying to ask in the book.

2. That ”˜The British’ ruled India for about 200 years is the simplest and most common perception that people hold in their minds. But there are two facts here (1) The East India Company was a mere merchant company and they lay the foundation for a rule that was then taken over by the Crown (2) The East India Company was brought to book, they were reined in, which is not a well- known fact at all.

Why do you think that these two facts are not as well-known as the simple perception ”˜The British ruled India’.

I don’t agree with the ”˜lay the foundation’. The”˜Raj’ proper only lasted ninety years ”“ 1858 to 1947. It was the tiny tip of the iceberg. Highly visible. The East India Company ruled for 250 years. It is not a true perception that they ”˜lay the foundation’, they were the edifice.

I think the Victorians spun the story they wanted to hear. Once the Victorian Raj was established they were embarrassed by the crude mercantile roots. They wanted it to be a story of a higher European civilisation coming and encouraging primitive peoples in Asia, bringing them to the light of enlightenment and so on”¦ which itself in essence is b”¦s”¦ (laughs). The truth is they came to a far richer country for profit, and because India disintegrated and the Mughal Empire disintegrated to be replaced by the anarchy, it was possible for the Company to hook up one by one the fragments of that empire.

3.It would be fair to say that power and profit is what drove the operations of the East India Company in the subcontinent. At a much later point the Crown took over. How do you think the ”˜British Raj’ was different to the way in which the East India Company operated?

First of all there was no reason for the company to exist but to make profit for its shareholders . That was the point of the East India Company. It was a profit making organisation of a bunch of merchants. It had no inherent interest in the long term well-being of the subcontinent. Its first impulse was to maximise profit and increase its assets by looting and plundering.

But in that period you also get a huge amount of collaboration with Indians. And the company is backed from the beginning (and this is what make its uncomfortable for Indians I think..) it was backed by the Marwari bankers, by Indian financiers, the Hindu bankers from Patna and Benaras, and they make two calculations.

One- The company is the safest place for their capital. If they loaned to the Company they are going to get their money back on time. Secondly, politically the East India Company is the least worse of many bad options by late 18th century when, the Marathas are running riot over central India, they raped Bengal, Tipu Sultan is regarded with fear and the Mughals are weak, and just as many people back a strong government to bring stability at a time of chaos even though they might not like what the government does. This is the calculation that many Indians made at this period. And you can very much see that by the time the big land reforms and permanent settlement came about in the 1790s by Lord Cornwallis, he created an entire class of Hindu landowners ”“ the Bhadralok Bengali families- the Maliks, the Debs, the Tagores and so on. The British break up the big Mughal out holdings and sell it off piecemeal to these new rich Hindu financier families, and so make these families, to some extent, dependent on the Company project. And so it is an important story in trying to understand how and why these different financial figures of the Bengali middle class made that decision, that to us seem unpatriotic or almost ”˜traitorly’, from the point of view of modern nationalism, but that’s not how people looked at it at the time.

So in the period of the company is corporate imperialism at its most ruthless, but you also get an extraordinary degree of collaboration and not just commercial and financial, because a third of the company men in 1780s were married to Indians and had Indian wives, the Royal Asiatic Society is taking enthusiastic interest in India’s past, James Princep, my forebear translates the (inscriptions on) Ashoka Pillar, Indian nationality is being discovered for the first time in 2000 years and there is this strange and forgotten closeness -sexual, economic, philosophical, academic, intellectual, and commercial. But it is a deeply exploitative period .

In the ”˜Raj’(period) it is a different set of parameters- you did have some sense that the British Government should be building this country, building communications, hospitals and universities. And in 1947, India’s economy is diminished, but it has the best educational system, the best communication system and the best health system in Asia.

But the Raj is deeply racist. There is complete separation of races and great racial injustice takes place.

So you have to in essence bear both these things in mind. If you were a beautiful Muslim Begum, you may well choose to marry a Company man, but if you were a rival warlord, the East India Company would loot your city, and rape your daughters. But in 19th century Raj you might be able to go to university under the umbrella of the Raj, if you were a trader you would be able to trade opium to China and make a fortune, but you would suffer daily racial discrimination.

So they are very different theories with very different pros and cons.

4.Nineteenth century India was a violent place with violence of all forms across social, economic and religious realms. But it was also a time replete with respect, acceptance and inclusion of different faiths and races. The Anarchy quotes numerous historical instances. And yet the youth of contemporary India today look back into history for their identity and belonging, and arrive at a highly distorted and dangerous version. So as a historian what do you have to say to them ?

This book is what I have to say to them. This is why I wrote the book. Because there are so many myths on all sides. There are many myths on the British side. My compatriot Phill believes that the Empire was glorious benign and somehow did not have any drawbacks ”¦.and it was all done for the ”˜good of the natives’. I have taken about six years to put a balanced view of what I think it was like and how different it was from the myths on every side and every nationality.

5. During your research for the book what were the most significant moments for you.

The most ”˜difficult’ bit was ultimately the most fruitful and satisfying was getting hold of the Mughal sources. I work in collaboration with a wonderful person called Bruce Wannell, who is an amazing scholar. It is really difficult to find these manuscripts and find the right bits. Wading through mountains of dusty old stuff which is very poorly catalogued and often even the curators of institutions are not clear about what is in them. These institutions like the Oriental Research Library in Tonk in Rajasthan are fairly basic spots. You are finding these Persian manuscripts in quite remote simple and fairly rural institutions which hold these incredible treasures. It’s a struggle to get permission to photocopy them, use them, find what you need and what you don’t need. But when Bruce then spins this stuff into gold, the incredible Fakir Khairuddin Illahabadi, Shahalam nama, Ghulam Hussain Khan’s ”˜Seir mutaqherin’”¦ When all these sources come in and finally makes it on to the page there is a terrific sense of achievement and pleasure.

And the biggest ”˜surprise’ was the degree of opposition to the Company in popular British popular press, like The Guardian reports on big pharma or evils of corporation. Very similar complaints in the 18th century . People are horrified that a corporation is doing this. Particularly when news comes, as it does in 1772, of the scale of the Bengal famine. At the same time these guys are returning with huge fortunes as one fifth of Bengal drops dead. They were irate. There were plays put on in the Hay Market with Clive (Robert Clive) caricatured as a ”˜vulture’. It is heartening to know though that our forebears were not liberals, that they were tough ruthless men who had no feeling for common humanity or human rights. The whole impeachment of Warren Hastings was a mess because they had the wrong guy, and facts were wrong and it was a joke in all sorts of ways, but it was about ”˜natural rights’ what they called in the 18th century for human rights. The basic principles were very notable and very encouraging.

6. There are four different Darlymples mentioned in the book. One is the author of the book. The other three -are they family members?

Yes . Stair Dalrymple is a great, great, great great uncle, born on the same property and brought up the same way as me. Alexander Dalrymple was his cousin, not a direct forebear. Alex brought the French and English match together after the capture of Pondicherry and realised that Australia was the next destination. He was not a fully able man and was not given the full command of the expedition. So he had a ”˜hissy-fit’ and somebody called Captain Cook led the expedition.

James Dalrymple – another cousin, not a direct forebear, married into the Mughal family in Hyderabad- to the great grand daughter of Noorjahan’s sister. So my family was exactly the sort of family who joined the company. They were minor Scots gentry with much greater aspiration than their purses would allow them. The Dukes and the Lords – the higher aristocracy ”“ didn’t join the company as it was so dangerous.”¦. They never came back”¦. You had to be slightly desperate to join the Company, but also grand enough to have the connections. The Dalrymples were exactly the sort of aspirational minor Scots gentry who fulfilled the need of the company generation after generation. And for me it very much seems in a sense”¦.. atoning (laughs).

Perhaps that’s why you are so drawn to Mughal history?

I do have a bit of Mughal blood and Bengali blood (.. Chandarnagar”¦) as well in me. When I initially came here (India) I felt instantly at home and I didn’t know any of this stuff about the genes until 20 years alter.

7. So much of what happened with the rise of the East India Company had to do with chance, luck and circumstances. How do you envisage an India had the East India company not succeeded the way it did.

Very difficult to say. Some options were – the French East India Company would have risen, or The Marathas, or with a slightly different stroke of luck Najaf Khan would have brought about a Mughal revival. Because enough people seemed to have valued it for them (the Mughals) to rise in 1857 to the Mughal Throne.

8. In the Introduction of the book you say this is not a complete history or economic analysis of the East India Company. What would you say to students of History who might want to refer to this source for History studies.

The East India Company is a vast subject that spans 250 years. But what I’ve chosen to focus on is how it conquered India particularly between 1750s and 1800s. There is a whole other book to be written on the Company in China, the opium wars, South East Asia , Singapore, and expedition to Australia. One could write 10 volumes on the East India Company. I have tried to answer this one question ”“”˜ How on earth did one company get in the position to conquer the Mughal Empire’? For a wider picture I would direct people to John Keay’s ”˜The Honourable Company’ which remains one of my favourite books.

9. India is a country that has captured your heart and mind and all your books are testimony to that. Very similar to James Kirkpatrick of ”˜White Mughals’. But he was enamoured by an India of a different time. What is it about the India of the last 25 years that has attracted you to her?

To say the negative first , there are times sitting in Delhi traffic jams in the heat of summer or when electricity is gone in the middle of the night or a week without wifi. I’m certainly not enamoured by the current political system, which I find alarming in all sorts of ways.

But I love this place just as much as I did when I was 18. For a historian its been a like a child in a freaky shop. Its an incredibly rich place to write about, and continues to surprise and amaze me every day.

It might be frustrating at times but it is never boring.

William Dalrymple will be speaking at :

William Dalrymple will be speaking at JLF Adelaide: https://www.ozasiafestival.com.au/events/jlf-in-adelaide/

UNSW John Clancy auditorium in Sydney https://www.centreforideas.com/event/william-dalrymple-relentless-rise-east-india-company

Short URL: https://indiandownunder.com.au/?p=14378